LIVER FLUKE – SIGNS, DIAGNOSIS, PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Liver Fluke (Fasciolosis) is a disease caused by the flatworm Fasciola hepatica. It affects a wide range of animals, including sheep and cattle, and although humans can become infected, although this is very rare in the UK. The disease is estimated to cost the UK livestock industry around £300 million every year due to liver condemnations, animal deaths, and reduced productivity.

WHERE DOES IT COME FROM?

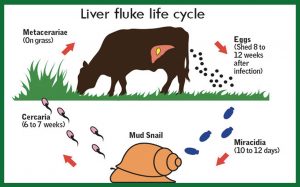

The liver fluke life cycle begins when eggs are passed onto pasture in animal faeces. These hatch and infect a small mud snail (Galba truncatula), where they multiply and develop. Under suitable wet conditions, immature fluke called cercariae leave the snail and encyst on vegetation as metacercariae — the highly infectious stage.

Animals become infected when they graze contaminated pasture. The ingested metacercariae develop into juvenile flukes that migrate through the liver, causing significant damage, before moving into the bile ducts where they mature into adults. Adult fluke produce eggs that pass out through the digestive tract and continue the cycle.

It takes approximately 10–12 weeks from ingestion of metacercariae for adult fluke to be present in the bile duct.

Unlike gut worms, animals do not develop immunity to liver fluke, meaning all ages are susceptible.

CLINICAL SIGNS

Disease is caused both by juvenile flukes migrating through liver tissue and by adult flukes feeding in the bile ducts.

SHEEP

Acute fasciolosis

Caused by large numbers of migrating juvenile fluke. Can lead to sudden death from internal bleeding or secondary clostridial infections (Black Disease). Signs may include extreme lethargy, abdominal pain, reluctance to move, and collapse. Most common in late summer and autumn.

Sub-acute fasciolosis

Fewer migrating fluke cause rapid weight loss, poor fleece quality, inappetence, weakness and depression. Death can occur without treatment. Typically seen in autumn.

Chronic fasciolosis

Caused by adult fluke in the bile ducts. More common in late winter and early spring. Signs include poor body condition, anaemia and bottle jaw (fluid swelling). Results from impaired liver function and inflammation.

CATTLE

Cattle typically develop chronic disease, shown by poor weight gain and anaemia. Sub-clinical infection can reduce milk yield. Diarrhoea is possible but usually linked to secondary Salmonella infection.

DIAGNOSIS – PREVENTION – TREATMENT

Diagnosis

Liver fluke can be detected through bulk milk, blood tests, or faecal testing. Different tests identify infection at different stages, so test choice depends on the time of year and level of risk.

Prevention

Fluke risk varies greatly between farms and even between fields. Wet, boggy or slow-draining areas are high-risk grazing zones. Identifying and, if possible, fencing off or avoiding known “flukey” areas during peak risk periods can reduce infection.

Treatment

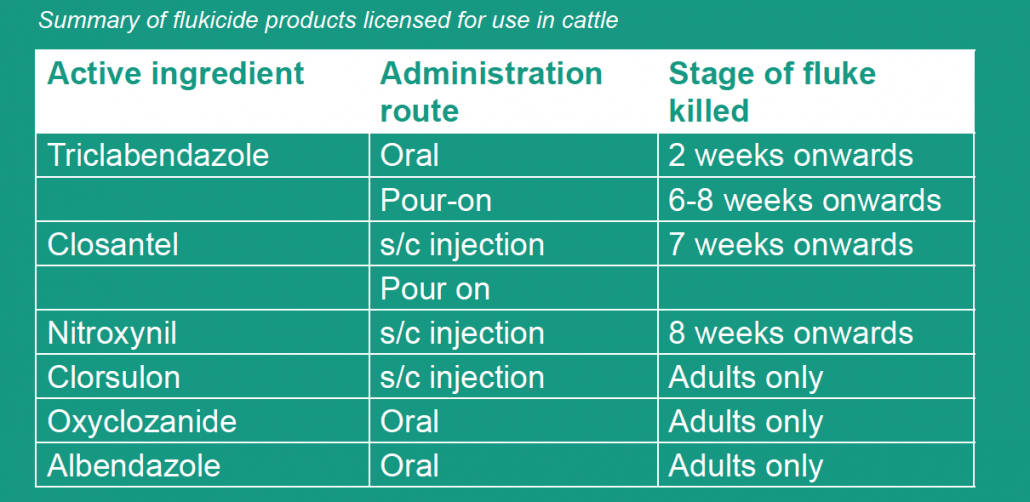

Choosing the correct treatment depends on the age and stage of the fluke present, as not all products are effective against every stage. Understanding seasonal risk and test results is essential when planning treatments.

Please get in touch for any information regarding fluke and its treatment.

Maedi Visna is a wasting disease causing chronic pneumonia. It is caused by a highly contagious virus. Most sheep are infected as lambs via colostrum or aerosol, however generally do not show signs until they are 4 years old.

Maedi Visna is a wasting disease causing chronic pneumonia. It is caused by a highly contagious virus. Most sheep are infected as lambs via colostrum or aerosol, however generally do not show signs until they are 4 years old. Ovine Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma is caused by a virus leading to a progressive and fatal infectious lung cancer of sheep. The virus is spread from infected sheep by aerosol and nasal discharge. It is often seen in older thin sheep. There is no treatment.

Ovine Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma is caused by a virus leading to a progressive and fatal infectious lung cancer of sheep. The virus is spread from infected sheep by aerosol and nasal discharge. It is often seen in older thin sheep. There is no treatment. Johne’s disease is caused by a bacterium which grows very slowly and lives for a long time in the environment. It is mainly spread through faecal contamination of feed and the environment, ewes also pass it to their lambs across the placenta and in colostrum. It is the same agent that causes Johne’s disease in cattle.

Johne’s disease is caused by a bacterium which grows very slowly and lives for a long time in the environment. It is mainly spread through faecal contamination of feed and the environment, ewes also pass it to their lambs across the placenta and in colostrum. It is the same agent that causes Johne’s disease in cattle. Border disease or hairy shaker disease is a virus which causes birth defects, barren ewes and abortion. It is from the same family of viruses as BVD in cattle.

Border disease or hairy shaker disease is a virus which causes birth defects, barren ewes and abortion. It is from the same family of viruses as BVD in cattle. CLA is a chronic bacterial infection of the lymph nodes resulting in abscesses. The bacteria often enters via cuts and is commonly spread through close contact when animals are housed or are trough fed. The disease can also be transmitted indirectly such as on shearing equipment.

CLA is a chronic bacterial infection of the lymph nodes resulting in abscesses. The bacteria often enters via cuts and is commonly spread through close contact when animals are housed or are trough fed. The disease can also be transmitted indirectly such as on shearing equipment. Lambing time is the most crucial part of the year for making your sheep business profitable. Lamb deaths from birth to 3 days old should be less than 7% however many farms range between 10- 25%.

Lambing time is the most crucial part of the year for making your sheep business profitable. Lamb deaths from birth to 3 days old should be less than 7% however many farms range between 10- 25%.

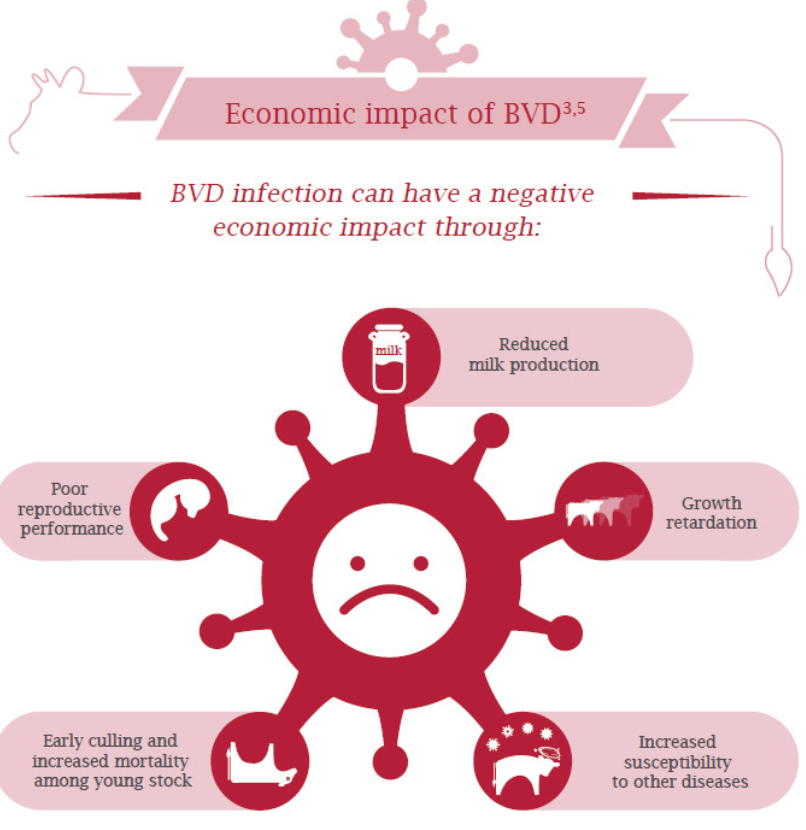

A new initiative has been launched to help farmers in England tackle BVD (Bovine Viral Diarrhoea).

A new initiative has been launched to help farmers in England tackle BVD (Bovine Viral Diarrhoea).